Off to the Cambridgeshire Fens this month with Lucy M Boston's classic story The Children of Green Knowe (1954), the atmospheric first book in her series of six.

The Children of Green Knowe is simply gorgeous: a sophisticated, eerie book that demands careful reading. The tale of young Toseland (Tolly), sent by train from prep school to spend a solitary, snowy and haunted Christmas with his grandmother in the family's ancestral home, arriving in a boat rowed across flooded meadows by an old retainer, is an appealing mix of one central story embellished with individual tales about the plague-dead (yet still present) children of the house and their animals - tales told by the old lady during firelit evenings before Tolly is packed off to bed to dream in his shadowy attic room. It's never quite clear where real life ends and magic begins.

Lucy Maria Boston (1892-1990) was born into a middle-class family in Southport, Lancashire in the north of England, the fifth of six children. Her father, who died when Lucy was six, was fervently religious and their home was crammed with items he had brought back from a visit to the Holy Land - painted friezes, lanterns, Moorish wooden arcades and other middle-eastern objects. It is this sense of a house full of fascinatingly magical things that she translates so well into the English surroundings of Green Knowe.

After going up to Oxford, Lucy left to nurse in France during WW1. She married in 1917, but the marriage ended in the 1930s and she worked as an artist in Europe for a few years. When her only son Peter went up to Cambridge University she followed him and, finding a run-down Manor House at Hemingford Grey near Huntington, she bought it, moved in and spent the rest of her life there; renovating the house and gardens, writing, making patchwork quilts, and enjoying welcoming curious passers-by to show them around. One of our group had been lucky enough to meet Lucy Boston themselves as a child.

Like one of her famous patchwork quilts, Lucy Boston weaves together sumptuous imagery with eerily evocative writing. Tolly goes out on a snowy morning: "In front of him, the world was an unbroken dazzling cloud of crystal stars, except for the moat, which looked like a strip of night that had somehow sinned, and had no stars in it."

There is Anglo-Saxon mythology, biblical imagery and Tudor history - and through it all we hear the haunting sounds of the flute played by a long-dead boy, and the ghostly hoofbeats of the thoroughbred horse that used to occupy the magnificent stables. There's terror too, when one of the ancient yew trees begins to come to life ...

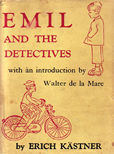

Lucy's son Peter's beautiful black and white line illustrations add to the pleasure of the book: incorporating the real-life objects from his mother's home they possess a slightly frantic yet eerie quality themselves: their close study is very rewarding. The front cover shows Tolly arriving by boat, with the haunting effect of the lantern shining on the flood waters and lighting up the ancient trees.

This is a beautiful, minimalist book which continues to reward with re-reading.

Next month we're back off to the United States when we'll be reading The Saturdays by Elizabeth Enright (1941), the first in the series of books about the Melendy children.