Today was spent tracking criminals through the back streets of Berlin with Emil (Tischbein) and his two dozen or more young friends, as we reviewed Erich Kästner's 1928/9 classic children's book, Emil and the Detectives.

Born in 1899 in Dresden, by 1927 Kästner had established himself in Berlin as a prolific and respected journalist and author, and one of the most important intellectual figures in pre-WW2 Germany. A pacifist who had served as a young soldier at the end of WW1, he published poems and articles in many important periodicals and newspapers. During the book burnings in Berlin's Opernplatz on 10 May 1933 he was personally denounced (amongst others) by Goebbels in what is now known as 'die Feuerrede' (the fire speech), and his works were thrown onto the bonfires - with the exception of Emil and the Detectives, which presumably stood alone in matching up to the regime's demand for "decency and morality in family and state".

Born in 1899 in Dresden, by 1927 Kästner had established himself in Berlin as a prolific and respected journalist and author, and one of the most important intellectual figures in pre-WW2 Germany. A pacifist who had served as a young soldier at the end of WW1, he published poems and articles in many important periodicals and newspapers. During the book burnings in Berlin's Opernplatz on 10 May 1933 he was personally denounced (amongst others) by Goebbels in what is now known as 'die Feuerrede' (the fire speech), and his works were thrown onto the bonfires - with the exception of Emil and the Detectives, which presumably stood alone in matching up to the regime's demand for "decency and morality in family and state"."Gegen Dekadenz und moralischen Verfall! Für Zucht und Sitte in Familie und Staat! Ich übergebe dem Feuer die Schriften von Heinrich Mann, Ernst Glaeser und Erich Kästner." (Against decadence and moral decay! For decency and morality in family and state! I hand over to the fire the writings of Heinrich Mann, Ernst Glaeser and Erich Kästner.)

Our knowledge of the ghastly events that were just around the corner for Emil, his friends and their families adds a real poignancy to this simple yet enormously satisfying story. 1920s Berlin comes happily to life as Kästner locates the action firmly in its bohemian café society. Music plays in the streets, there's the smell of frying sausages in the air and the villain enjoys his coffee and a cigarette at a table in the famous Café Josty (the pre-war meeting place for Berlin's writers and artists which was destroyed during WW2 and has been reincarnated in the Sony Centre, one of Berlin's modern landmarks).

The boys of 1920s Berlin had enviable freedom: unhampered by over-anxious parents with mobile phones they roamed the streets having wonderful adventures, while still managing to be incredibly polite to grown-ups and thoughtful of each other. They are largely unconcerned by social differences: Emil is a country mouse in town, but is welcomed by the streetwise young Berliners. The children - more than a hundred of them by the end of the book - inhabit their own exciting world and operate just under the adult radar; free to come and go, they have adventures that turn out well for all concerned, while a slice of apple cake and a hot chocolate is fair reward for their efforts.

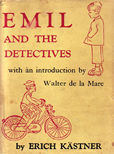

Wittily illustrated by Walter Trier (an anti-fascist who was also bitterly opposed to - and by - the Nazi regime), and with Kästner's occasional humorous asides and sly insertion of himself into the story, adult readers are kept as amused as their younger audiences, and the book is refreshingly free of moralising (apart from Grandma's outdated exhortion to "always send cash through the post"). There's even the mandatory comic policeman who can't remember Emil's surname. However, Walter de la Mare's lengthy introduction was universally condemned as a dreadful plot spoiler!

There was some discussion of the quality and nature of the English translation from the original German (we were reading Eileen Hall's 1959 version), with the view expressed by those of the group who are German speakers that the book is more genteel in tone than would have been the case. Perhaps there's an opportunity for a new translation of Emil that uses a more authentic voice and replicates the Berlin street slang of the original? The portrayal of Pony, the only girl in the story, although understandable for its time, was something of a disappointment. Despite her seeming liberation at first, with her bicycle and her brisk approach to boys, she remained firmly in the role of home-maker and head chef.

All that said, we loved our brief stay in pre-war Berlin. In comparison to the more sophisticated stories that children read today, Emil and the Detectives is a charming, simple yet fast-paced story that ends well and leaves the reader satisfied that all's right with the world.

At our next meeting we will be reviewing Joan Aiken's historical novel for young adults, Midnight is a Place (1974).

At our next meeting we will be reviewing Joan Aiken's historical novel for young adults, Midnight is a Place (1974).