The Montagues and the Capulets; the Sharks and the Jets? This month we came face to face with Diana Wynne Jones' magical Montanas and Petrocchis in The Magicians of Caprona (1980), the third book in her Chrestomanci series.

The two warring Italian families live in their sprawling, fortified spell-houses in the city state of Caprona, located somewhere between Florence, Siena and Pisa and set in an indefinable time - a "world parallel to ours, where magic is as normal as mathematics and things are generally more old-fashioned". Caprona is rather like Lyra's Oxford in Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials trilogy (1995-2000). The tourist buses circulate, while the families ride in magical horse-drawn carriages and work at spells in the Scriptorium. Sworn enemies, they do everything they can to outdo one another while firmly believing the worst of each other. But while they are fighting, they fail to notice that their city is falling under an evil enchantment. Young Tonino is the only person in the Montana household who wasn't

born with an instinct for creating spells. His ability to communicate with cats might help Caprona - but only if he can cooperate with a girl from the hated Petrocchi family.

The book has a rather lengthy beginning, which required some application and stubborn persistence, with its numerous Italianate characters ("The Montanas were a large family") all delaying the narrative and crying out for a family tree to be included by a helpful publisher. But right from the bright and colourful beginning, with gorgeous descriptions reminiscent of the market place in Angela Carter's short story The Kiss (1985), Wynne Jones' unique style, her powers of description and her humour shine from the pages.

"The Old Bridge in Caprona is lined with little stone booths, where long coloured envelopes, scrips and scrolls hang like bunting. You can get spells there from every spell-house in Italy. If you find a long, cherry-coloured scrip stamped with a black leopard, then it came from Casa Petrocci. If you find a leaf-green envelope bearing a winged horse, then the House of Montana made it."

The story gradually darkens with family feuds, terrifying magical street battles, and a Punch and Judy sequence that plunges the protagonists into a darkly frightening place from which they must escape. Benvenuto, the wise and independent old cat, provides Tonino with a welcome familiar in the tradition of Carbonel (Barbara Sleigh, 1955), Orlando (Kathleen Hale, 1938) and - rather more sinister - Blackmalkin (John Masefield, The Midnight Folk, 1927). There are overtones of J R R Tolkien too - one of Wynne Jones' tutors at Oxford University where she was a student of English Literature.

The story is told from Tonino's single narrative viewpoint. This is a

useful technique, which allows a 'reveal' when a weak character (viewed

from the narrator's perspective) is suddenly seen in a different

light. "Re-reading pays dividends" someone said, and for those who did

re-read the book, this offered an the opportunity to appreciate the

hidden dimensions of all the characters and to see the story's many

different levels more clearly.

With her own memories of a difficult childhood, growing up largely without books, Wynne Jones emphasises the importance of strong family relationships

and this is a story that will help children to understand that the

process of growing up and breaking out can make them stronger in the

end.

Alongside Magicians of Caprona, we read the transcript of a talk about Diana's work given by her son, the academic Dr Colin Burrow of All Souls', Oxford. It was broadcast on BBC Radio Three on 4 July 2011 as part of a series The Essay: Dark Arcadias.

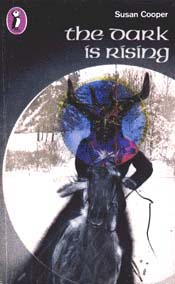

Further recommended reading: Four British Fantasists: Place & Culture in the Children's Fantasies of Penelope Lively, Alan Garner, Diana Wynne Jones and Susan Cooper, Charles Butler, Scarecrow Press, 2006.

For our next meeting we will be reading Mary Treadgold's Carnegie-winning book We Couldn't Leave Dinah (1941), a book that extends the conventional "pony genre" to incorporate a darker perspective of life during World War 2 - this time on an island under occupation, rather than in the cheerfully distant New York of the Melendy family.